What’s the old saying about a good engineer being done when everything is taken away? I’m certain you can apply that adage completely to Terry Cavanagh’s games. Another that would fit quite well is ‘easy to learn, hard to master.’ I think a game that defines itself so simply and elegantly as Super Hexagon or VVVVVV leaves little room for flaws and leaves a much stronger impression as a quintessential game.

The design of VVVVVV starts with a platformer, but without all the baggage that ‘platformer’ comes with - no health bars, no points, no plentiful item pickups (save for a few aptly named ‘trinkets’), no lives, not even jumping. Simply movement in a 2D space, but with one element thrown in: the ability to reverse gravity. The game takes this mechanic and explores it fully - what if there was a barrier which would trigger the gravity swap upon contact? What if you had to bounce between multiple barriers repeatedly to reach an objective? What if you threw in some laterally moving obstacles into the mix?

Cavanagh illustrates this ideal of fully exploring a simple combination of mechanics on his Reddit AMA, when he is asked for his opinion on the Veni Vidi Vici puzzle, where the player had to rapidly navigate a narrow and dangerous passage as they fall upwards, then again as they fall downwards.

‘Veni Vidi Vici had to exist, basically. I didn’t make it because I thought it would be fun, or because I thought anyone would honestly want to do it. I made it because the world demanded it; because it was a logical place for the design to extend.’

Beautiful! If the game is thought of as a discrete set of mechanics, where every possibile combination of those mechanics are explored, then leaving out a puzzle such as Veni Vidi Vici would leave the game incomplete.

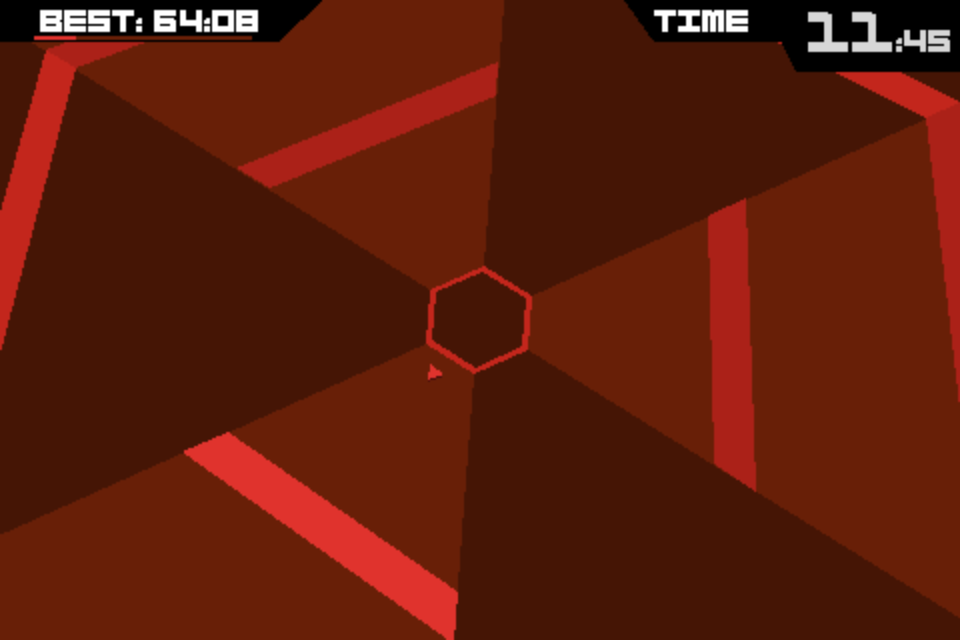

Super Hexagon, though it plays very differently, still feels like it is made of the same DNA as VVVVVV. Part of this is due to the ultra-simple retro visual aesthetic and music, but it shares the minimalistic approach to game design, too. A player-controlled triangle rotates around the center of the screen, avoiding obstacles that come from the outer edge. (You can play a simpler online version of the game at Kongregate.) Quick reactions are necessary, and muscle memorization as well as rote learning help players past their first five seconds, then ten, and then possibly even a full minute or two. If this sounds like oddly short gameplay sessions, consider that the game is on iOS, where as Pocket Attack notes one or two minute gameplay sessions often work best. Of course, the beauty of the game is every time you collide with a barrier and restart, you’ll feel that you were so close to making it that you’ll end up stringing together enough tries to fill half an hour.

Where Super Hexagon differs from VVVVVV and the simplicity-at-all-costs design style is the almost psychedelic visual effects. In addition to rapidly dodging incoming obstacles, players must deal with a rapidly pulsating, spinning, and skewing play field. This conceit adds to the difficulty, and while initially off-putting it’s easily learned and works well.

Both games serve as excellent examples of elegance in game design. Games too often seem to focus on more, more, more with each new sequel and Cavanagh clearly recognizes the beauty of simplicity in games.

Comments